Gully Foyle is my name

And Terra is my nation

Deep space is my dwelling place

And death's my destination.

Outline

Gully Foyle is marooned 170 days in space on the wreck of the Nomad with thought or hope other than that of day-to-day survival. None, that is, until a passing ship, the Vorga, spurns his distress signals. In his despair Gully is changed into a driven man, one that will not stop until he has his vengeance on those that left him to die.Over the course of the story, Gully changes. Initially on the outside from the facial tattoos given him by a lost tribe deep in the asteroid belt, then on the inside as he forces himself to change to achieve his goals. And the final change? Well you will just have to read the story for that one...

Author

Alfred ‘Alphie’ Bester was born in 1913 in Manhattan, New York, the second child of James (Austrian descended first generation American) and Belle (Russian Jewish immigrant). After university briefly studying law, Alfred started writing science fiction while working in public relations, winning in 1939 a place (and $50) in Thrilling Wonder Stories with his piece: The Broken Axiom. It is popularly reported that Robert Heinlein had decided against entering that same competition as the prize money was less than he could get from selling his story direct to Astounding Science Fiction.Backed by a growing number of stories published in this and other magazines, Bester gained a place in 1942 at DC Comics, writing Superman, Green Lantern and other titles. In 1946 he moved into radio, writing scripts for shows; then two years later doing the same for television.

In 1950 he started writing science fiction again, publishing short stories throughout the decade in Astounding and Galaxy Science Fiction. It was during this period that he wrote The Demolished Man, which won the Hugo Award in 1953; the first ever presented. In the same year he also published Who He?, a thriller set in 50s television, and followed with The Stars My Destination in 1956.

In 1959 Bester took a twelve year break from SF while he was the he senior editor of the Holiday magazine. In 1973 he returned to SF, publishing a number of Hugo nominated short stories and novels before his death in 1987.

Bibliography & Awards

Highlights:1953: The Demolished Man (winner of the first Hugo award)

1953: Who He? Also published as The Rat Race

1954: Star Light, Star Bright (retro Hugo nominated)

1954: Fondly Fahrenheit

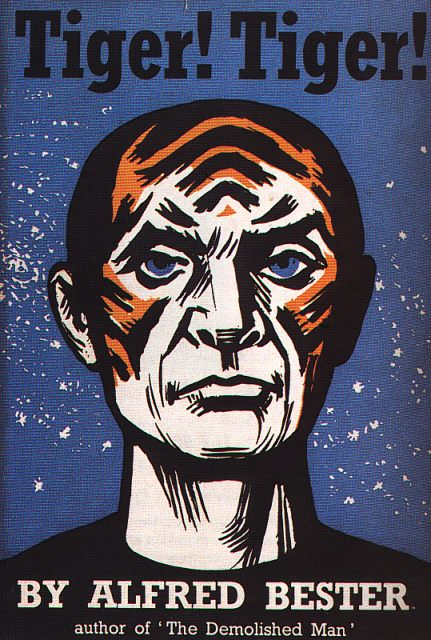

1956: The Stars My Destination also published as Tiger! Tiger!

1958: The Men Who Murdered Mohammed (Hugo nominated)

1959: The Pi Man (Hugo nominated)

1959: Murder and the Android (TV adaptation of Fondly Fahrenheit – Hugo nominated)

1975: The Computer Connection (Hugo nominated)

1975: The Four-Hour Fugue (Hugo nominated)

1980: Golem100

1981: The Deceivers

1987: Science Fiction Writers of America Grand Master award

1991: Tender Loving Rage (posthumous)

1997: Virtual Unrealities (posthumous)

1998: Psychoshop (posthumous)

2000: Redemolished (posthumous)

2001: induction into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame (posthumous)

Context

The Golden Age of SF

The Golden Age of SF is generally held to be the 1940s and 50s, lead by John W Campbell during his stint as editor at Astounding Science Fiction. Campbell led the movement away from the “pulp” stories of the 20s and 30s, epitomised by EE “Doc” Smith and the early Space Opera, and into the realms of what we now know of as Hard SF. Here the material sciences were emphasised, whether physics, chemistry, or electronics, with less concern placed on characterisation. I suspect that it is no coincidence that the Golden Age is also that of the huge technological advances as a result of the Second World War, whether rocketry or atomic weapons: the SF authors now had something firm to work on, space flight was finally within reach. The stars of this age (excuse the pun) are Robert A Heinlein, Arthur C Clarke and Isaac Asimov.

The Golden Age of SF is generally held to be the 1940s and 50s, lead by John W Campbell during his stint as editor at Astounding Science Fiction. Campbell led the movement away from the “pulp” stories of the 20s and 30s, epitomised by EE “Doc” Smith and the early Space Opera, and into the realms of what we now know of as Hard SF. Here the material sciences were emphasised, whether physics, chemistry, or electronics, with less concern placed on characterisation. I suspect that it is no coincidence that the Golden Age is also that of the huge technological advances as a result of the Second World War, whether rocketry or atomic weapons: the SF authors now had something firm to work on, space flight was finally within reach. The stars of this age (excuse the pun) are Robert A Heinlein, Arthur C Clarke and Isaac Asimov.New Wave

With the 1957 launch of the Sputnik satellite closing the gap between speculative fiction and reality, and the feeling that SF was becoming clichéd, fans and authors began to desire explorations of new themes and directions. As Brian Aldiss says in his seminal Billion Year Spree. The History of Science Fiction:“On the whole, the props of SF are few: rocket ships, telepathy, robots, time travel, other dimensions, huge machines, aliens, future wars. Like coins, they become debased by over-circulation ... in the fifties, ... writers combined and recombined these standard elements with a truly Byzantine ingenuity ... but there were signs even then that limits were being reached. By the sixties, the signs could not be ignored.”What was need now were not stories of technology, but stories about the effects of technology on people and the way that they live. The popular backlash against Hard SF and the move into the Soft SF topics of psychology, sociology, religion, sex and drugs (but little rock and roll) was lead by the likes of Michael Moorcock (then editor of the New Worlds magazine) and JG Ballard: “it is inner space, not outer, that needs to be explored”. Some of the old school authors joined the movement; Heinlein’s 1961 classic Stranger in a Strange Land marks both his Middle Period and his entry to the New Wave.

When the New Wave authors lead the revolution against the old establishment, they found that Alfred Bester was already there waiting for them. In both his major 1950s SF works, the character arc is central to the story. In The Stars My Destination the central theme is the effect of vengeance on the avenger, and in The Demolished Man the psychological breakdown caused by committing murder in a society of mind-readers. Bester was writing Science Fiction in the Golden Age, but he was already ahead of his time.

Cyberpunk

With the passing of 60s radicalism, the end of the moon landings, loss of the Vietnam war and the harsh realities of the oil crisis, the New Wave authors were absorbed into the mainstream: Hard SF and Space Opera were back. But in the same way that age of disco and prog rock were ended by punk rock, so the direction of SF was changed by the emergence of Cyberpunk in the early 80s. The gleaming spires of the future were replaced by “high tech and low life”, information technology, cybernetic enhancements and mega-corporation dystopias. While there was no computerisation in Alfred Bester’s work in the 50s (it was still mostly hidden in military research establishments), the Cyberpunk authors recognised and built on Bester’s groundwork established 30 years earlier. William Gibson, author of Neuromancer and one of the architects of the cyberpunk movement, said that “I can’t remember having met an SF writer whose opinion I respected who failed to share my enthusiasm for Alfred Bester’s work”. As Neil Gaiman wrote in his essay Of Time, and Gully Foyle: “The Stars My Destination is, after all, the perfect cyberpunk novel.”Main Themes & Motifs

Revenge

Revenge

The Stars My destination is essentially a book about revenge, whether its effect on the person caught up in its execution or those subject to collateral damage. Gully is initially changed from a mindless drone to a mindless predator, then a showman and finally a rounded and compassionate human being. It is not a recommended route, Gully was lucky to survive, as were his targets.Gully was not alone in seeking revenge: Olivia Presteign sought to pay back all of humanity for her blindness and isolation, the Outer Planets on the Inner for economic collapse, the Inner Planets on the Outer for the nuclear attacks, Lindsey Joyce on herself for her crimes. All were changed, some for the better, some for the worse, but none would ever be the same again.

Jaunting

A central motif in The Stars My Destination is that of teleportation, which goes by the name of jaunting. Named after the fictional scientist Dr Charles Fort Jaunte, who accidentally discovered that he had the innate ability during a laboratory fire, the technique has been refined and taught across most of humanity in the Solar System.It was not without its cost though. Who will drive a car or take then train when they can jaunte? Transportation systems became redundant, along with the supporting industries such as petroleum (this would be such a popular discovery today). With whole industries collapsing, the trade between the inner and outer planets suffered so much that it led to inter-planetary war.

War

Written just ten years after atomic bombs ended the Second World War, the book has an undercurrent of fear of nuclear destruction symbolised by PyrE. While Asimov at the same time viewed atomic weapons as essential for civilisation in his Foundation trilogy, Bester saw in them the potential for universal destruction that we need to resolve and come to terms with. War had recently engulfed the world and threatened to again, but this time promising few survivors. Nuclear bombs had as much a hair-trigger as the PyrE, though these thoughts came from presidents not psionics. The name itself hints at Bester’s antipathy: funeral.It is interesting to note that Gully’s predicament was based on an actual event during the Second World War. A shipwrecked mariner survived in the pacific for four months, ignored by passing ships that feared that he was a decoy to lure them into the sights of a hidden submarine.

Commerce & Corruption

“This was a Golden Age, a time of high adventure, rich living and hard dying...but nobody thought so. This was a future of fortune and theft, pillage and rapine, culture and vice...but nobody admitted it. This was an age of extremes, a fascinating century of freaks...but nobody loved it.”The rich are extravagantly retro; the offices drably so. All SF books are products of their time and have to be read as such. Some scenes and details have not dated well, but much is timeless. It reads as if the world has reverted to the era of cold-war rock and roll, but with a proto-cyberpunk overlay of human enhancement and corporate corruption.

With jaunting so common, security is now much more difficult. Houses are close off to the outside world, rich properties are protected by labyrinths to disorientate visitors, women are locked away to “protect them”. With easy mobility, society has more stratified. Squatters and looters now roam the planet while the rich flaunt their wealth by using conspicuously expensive mechanical transports, all scenes reminiscent of the Great Depression: Bester’s formative years.

Literary influences

There can be few SF works that have as many anchors in literature as this. From Shakespeare to Blake via folk poetry, Bester’s writing is grounded in the past while looking to the future.The story of Gully, or Gulliver Foyle to give him his full title, is in many respects a reworking of Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo (1844), but achieving the same result in a mere quarter of the pages. 1000 page plus novels are not a new invention. Gully’s name also possibly points a reference to Jonathan Swift’s political satire of 1726: Gulliver’s Travels, and its theme of whether men are born corrupt or become corrupted.

The opening to part two of the story quotes from Tom O’Bedlam, inmate of the madhouse: “With a burning spear and horse of air, to the wilderness I wander”. But this is just Gully’s persona, a cover that holds a grain of truth: “With a knight of ghosts and shadows I am summoned there to tourney, ten leagues beyond the wide world’s end – methinks it is no journey”. He is hiding one madness with the pretence of another.

Without a doubt, one of the major influences on this story is William Blake’s 1794 poem The Tyger (commonly rendered The Tiger today). While his Geoffrey Fourmyle incarnation is Tom O’Bedlam, The Tyger perfectly describes Gully’s true character and fate

The Tyger

Tyger! Tyger! Burning brightIn the forests of the night,What immortal hand or eyeCould frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skiesBurnt the fire of thine eyes?On what wings did he aspire?What the hand dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder and what art

Could twist the sinews of thine heart?

And when thy heart began to beat

What dread hands and what dread feet?

What the hammer? What the chain?

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? What the grass

Dare its deadly terrors clasp?

When the stars threw down their spears

And watered heaven with their tears,

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the lamb make thee?

Tyger! Tyger! Burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

Synaesthesia

The concussion from the PyrE explosion gave Gully a real neurological condition: synaesthesia. It is a confusion and crossing of the senses, where the stimulation of one leads to experience of another.“Colour was pain to him...touch was taste to him...smell was touch...”Common forms include associations of colour with numbers, letters, or days of the week. There are recorded cases of synaesthetic musicians who know what to play because the music smells right, artists who can quite literally paint a poem, speakers who cannot say certain words because of their taste on the tongue. It is not known if it is more common among creatives, but certainly the cross-connectivity will encourage creativity, which is a different way of looking at things.

Synaesthesia has been used a number of times in literature in a metaphorical sense: a loud shirt, a bitter wind. Bester though was one of the first to directly describe the synaesthetic experience. But while the description is literal, Bester also makes it gorgeously poetic. Ray Bradbury opens Fahrenheit 451 with a burst of poetic prose, Bester saves his until the fiery climax. Figurative, factual, beautiful, terrible; it is a trick difficult to pull off, yet Bester does it with ease. Bester (and Bradbury) stand in stark contrast to their Golden Age contemporaries in their mastery of the English language.

“Hot stone smelled like velvet caressing his cheek. Smoke and ash were harsh tweeds rasping his skin, almost the feel of wet canvas. Molten metal smelled like blows hammering his heart, and the ionization of the PyrE explosion filled the air with ozone like water trickling through his fingers.”

Concrete Poetry

Unlike most of his fellow SF writers who were steeped in the sciences, Alfred Bester’s tapping into literature gave his books another unique edge, including his use of a style called Concrete Poetry to explain aspects of the story. Here the shape of the words on the page is as important in conveying the information as the words themselves.For example, here is a telepathic discussion in The Demolished Man, in the form known as a “basket”:

With Gully Foyle’s synaesthesia attack, Bester uses the Concrete Poetry techniques to further convey Gully’s warped senses and confusion.

Good authors are always trying to “show not tell”; Bester took it one step further.

Of course, a negative aspect of this innovative use of embedded graphics is that it makes it far more difficult for publishers to reformat the text for a new generation: the old style fonts will be with Bester for a while.

Gully Foyle

Author's Portrayal

SKILLS: noneMERITS: noneRECOMMENDATIONS: none

He was a no-man on the Nomad, though mad he truly was. Scarred in face and mind by his experience of marooning and abandonment and rescue; consumed by a burning hatred for those who left him to die until there was no humanity left - only the predator. Tiger of face and of mind, Gully Foyle was the foil to the richest man of the twenty-fifth century. He had no purpose except survival until the Vorga gave him a fire of life; the hidden treasure of the Nomad giving him the fire of death.

But his quest makes him grow and change. By the time he finds his true object of hatred it has already become his true love. He starts not even black and white but only black, yet is finally colour against the grey. In the end he finds ambiguity, complexity, and his humanity. His redemption holds a paradox at its heart: the ultimate loaner saved himself through those he betrayed; the unlovable loved. It was impossible, but the impossible was what Gully did best.

Reader's Response

The future here is not bright, nor orange; it is dark, red and black. There are no heroes, no knights. Everyone is on the make for themselves, traitors to all except their own gain. Gully is an antihero, who demands our empathy because of his simplicity and endurance, but at the same time repulses us because of his violence and guttural nature. Which of us could survive like he survived? But which of us would seek vengeance like him? He is rage personified. His antagonists are immoral; he is amoral. He is hate focused, with no thought for those in the way. He is an arrow.By part two of the book he has become more of a sympathetic character. His disguises and the aftermath of his tattoos force him to attain self control. Though still driven by the need for revenge, he does start to achieve the moral high-ground over his foes and forgiveness from those he has wronged in his quest. By the end we are totally on Gully’s side.

Critical Response & Legacy

In his peak time in the 1950s, Alfred Bester wrote two SF novels and a number of short stories. Although he did not produce a large quantity, the influence of his quality resonated for decades to come. His first novel, The Demolished Man, won the first ever Hugo; The Stars My Destination would have been eligible for the 1957 Hugo, except that year they awarded them only to periodicals. Both these novels are recommended in Andrews and Rennison’s 100 Must-Read Science Fiction Novels, which is a rare honour as most authors are allowed only one.

Bester’s invention of the term Jaunte for teleportation was memorably used in the 70s TV series The Tomorrow People, and by Stephen King in his short story The Jaunt. King also explicitly pays tribute when his character Scott Landon in Lisey’s Story dedicates his new library to Alfred Bester.

In the TV series Babylon 5, the psi-cop character Alfred Bester is a homage to his book The Demolished Man. Another reference is in F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre’s short stories about a time-travelling criminal repeated is foiled by a scientific principle called “Bester’s Law”: a time-traveller who attempts to rewrite the past can only alter his own timeline.

Other top SF authors have heaped direct praise on The Stars My Destination:

- Robert Silverberg: “On everybody’s list of the ten greatest SF novels”

- Samuel R. Delany: “Considered by many to be the greatest single SF novel”

- Joe Haldeman: “Science fiction has produced only a few works of actual genius, and this is one of them”

Conclusion

“The Stars My Destination” is a title riddled with ironic hope. Like Neil Gaiman, I prefer the original British title: “Tiger! Tiger!”. This is partly because it was under this title that I first read this book, but mostly because it better fits the character of Gully Foyle. Revenge was his destination, not the stars. Well, at least initially.With Gully Foyle, Alfred Bester created a character that at first is utterly repulsive, yet still engaging; then took him through a wild, imaginative, and feasible arc into the final, super-human yet utterly human result. Along the way Bester exposed the fears and corruptions of 50s American culture: dark, scared, but ultimately hopeful for the future. He also inspired SF writers and literary movements for decades to come. The Stars My Destination, or Tiger! Tiger! if you prefer, is truly one of the great books of the science fiction cannon.

Gully Foyle is my name

And Terra is my nation

Deep space is my dwelling place

The stars my destination

|

| (c) Chris Moore |

Peter Debney; 2010

1 comment:

@Peter Nice analysis of _The Stars My Destination_.

I knew Bester, back when, and he fit the description one woman once gave him of "Alfie Bester is what I always thought a writer was till I actually met some!" :-)

He was cultured, urbane, and cosmopolitan, and the late James Blish called him "one of the nicest guys you will ever meet whose feet still touch the ground when he walks." That was a fairly accurate portrayal.

He described himself as the model reader of Holiday Magazine - educated, affluent, with *expensive* hobbies - just who the advertisers wanted to reach. He left Holiday when Downe Publications relocated to Indianapolis, and lifelong New Yorker Bester declined to go with it. He returned to writing SF. He recounted a conversation with H. L. Gold when he stopped writing SF, and Gold told him "You said what you had to say." He found more things to say when he returned.

______

Dennis

Post a Comment